Death in Cherry Valley: Native American Irregulars in Upstate New York

After the British evacuated their troops from Boston in March of 1776, few battles were fought in New England aside from the skirmish at Bennington.1 In some respects, New England was spared from wholesale destruction. A very different war was waged in the west.

In Upstate New York, British forces, American Rebels, and their Indian allies fought a prolonged and brutal frontier war across thousands of square miles. Skirmishes and lightning raids devastated the countryside and terrorized residents, tribal and colonial. Homes and farmland were destroyed. Civilians were caught in the crossfire.

Repercussions of Saratoga

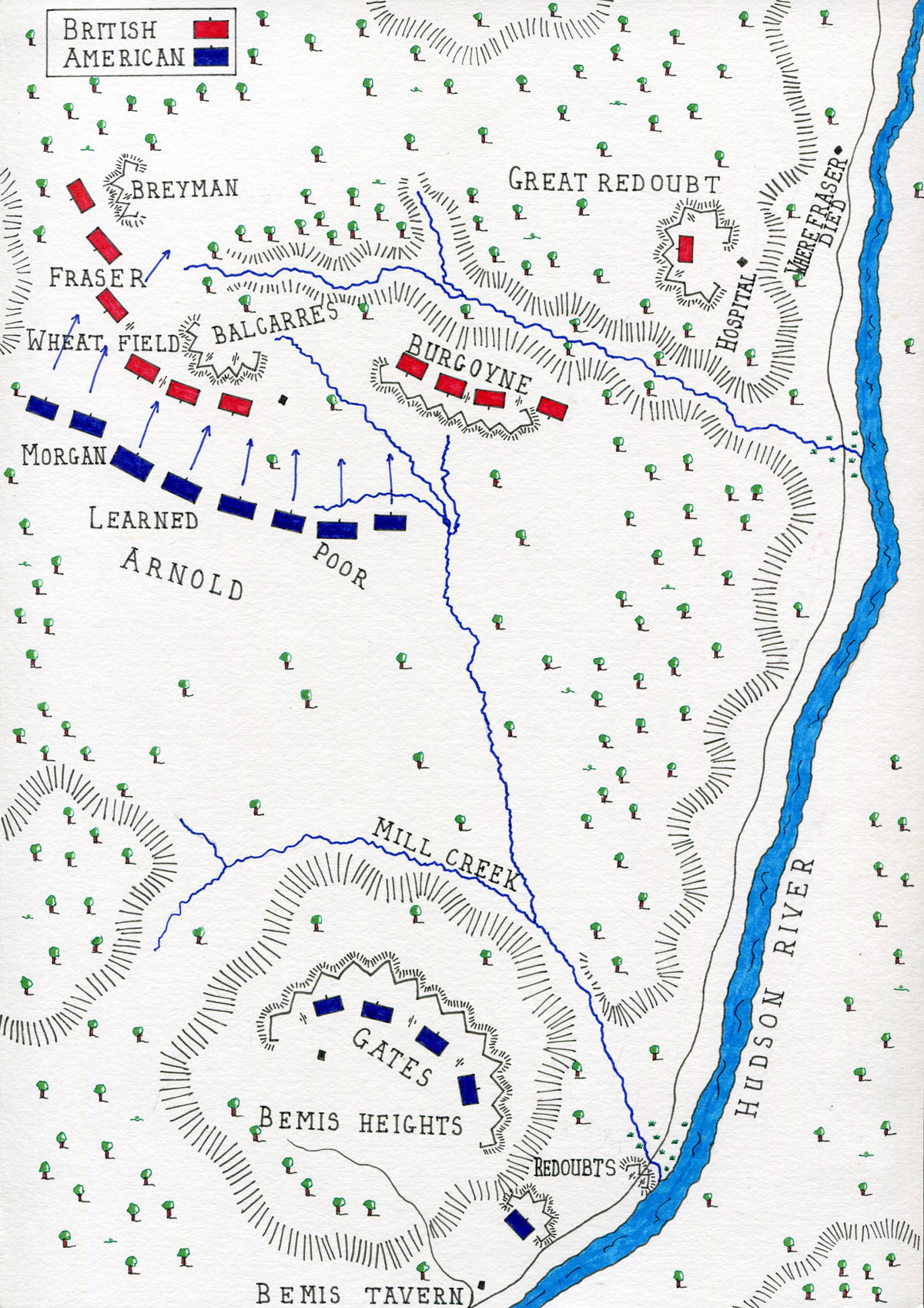

The Battle of Saratoga is considered to be a turning point in the American Revolution. General John Burgoyne and around ~7,500 British regulars surrendered to a large American force led by Horatio Gates in October 1777. Covertly, Gates actually tried to use his victory as a pretext to oust George Washington as commander in chief and take his place — this obviously didn’t work out for him.2

Saratoga was a big boost to morale. Crucially, it earned the fledgling American government an official alliance with the French, and under-the-table support from the Dutch and Spanish. But there were drawbacks.

The British Army shifted its priorities to the defense of Canada, and strikes on the southern colonies. Their manpower resources were spread thin.

General Guy Carleton, who now commanded Britain’s northern department, was no stranger to bloodshed. He had fought in the French & Indian War and was wounded on the Plains of Abraham and in combat off the coast of France in 1761.3 Now that the army was moving elsewhere, he needed new recruits.

Carleton was officially barred from employing Indians in military service outside of Quebec. He had been personally opposed to recruiting tribal warriors in the first place. When he met with the Six Nations in 1775, the General forbade them from taking the war-path. The following year, Carleton even sent away a group of Ottawas who had traveled to Montreal to offer their services as mercenaries.

Carleton’s official justification was that Indian volunteers were undependable in combat. In private, Carleton feared brutality and indiscriminate killing. But after Saratoga, he and his lieutenants were authorized to wage a different kind of campaign, and did employ Indian allies in combat alongside loyalist irregulars, as they’d done during the French & Indian War several years earlier (1754 - 1763).

Native Alliances

The Six Nations of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy were one of the most powerful Native polities on the continent. They had remained neutral when war broke out. Once the Americans declared independence, the tribes split, with some voices urging continued neutrality and others advocating for war.

A crucial force in this discussion was Joseph Brant, whose Mohawk name Thayendanegea means “He places two bets together.” Brant advocated for joining with the British, correctly pointing out that Washington himself had been an important investor in the Ohio Company, which pushed an enormously disruptive European settlement into the Ohio river valley. This may have even helped spark the French & Indian War.4

Brant predicted that should the Americans win control of the country, any new independent government would not respect native rights to land. In many respects, those predictions proved true.

Joseph Brant was a fascinating figure in his own right, and one of the most famous Native Americans of the late 18th century (I plan to cover more of his story in another segment). It is important to mention that both Washington and Brant owned slaves. Brant was born Mohawk, but European practices had an significant influence on him.

Joseph’s sister, Molly, married Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs in New York, and a key figure in the French & Indian War. You can still visit Johnson’s home in Johnstown, New York, which is known as Johnson Hall (the town itself was founded by him). William Johnson also had a major influence on Brant’s leadership among the Mohawks.

Brant’s lobbying was successful. Four of the six member nations joined with the British, including the Seneca, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Mohawk tribes. The Oneida and Tuscarora sided with the Americans.

Volunteers of America

Brant received a Captain’s commission and established a base of operations at Onaquaga (today, Windsor, New York) near the Pennsylvania border. In the winter of 1777, just months after the rout at Saratoga, he started recruiting a mixed force of loyalist and Iroquois men. They became known as “Brant’s Volunteers” and grew to a partisan force of around 300 men.

Brant ordered his men to identify themselves as loyalists by wearing yellow lace on their hats. His non-Indian volunteers frequently painted themselves as indigenous warriors. The all-volunteer force received no pay, and no official provisioning from the British. Instead, they relied on plunder and foraging to supply themselves. This would prove problematic for maintaining control of the force, but would earn him a fearsome reputation amongst continentals and their commanders.

Wilderness War

After the spring thaw, Brant started to venture north, raiding towns and villages. His volunteers stole cattle, burned houses, and killed non-combatants.

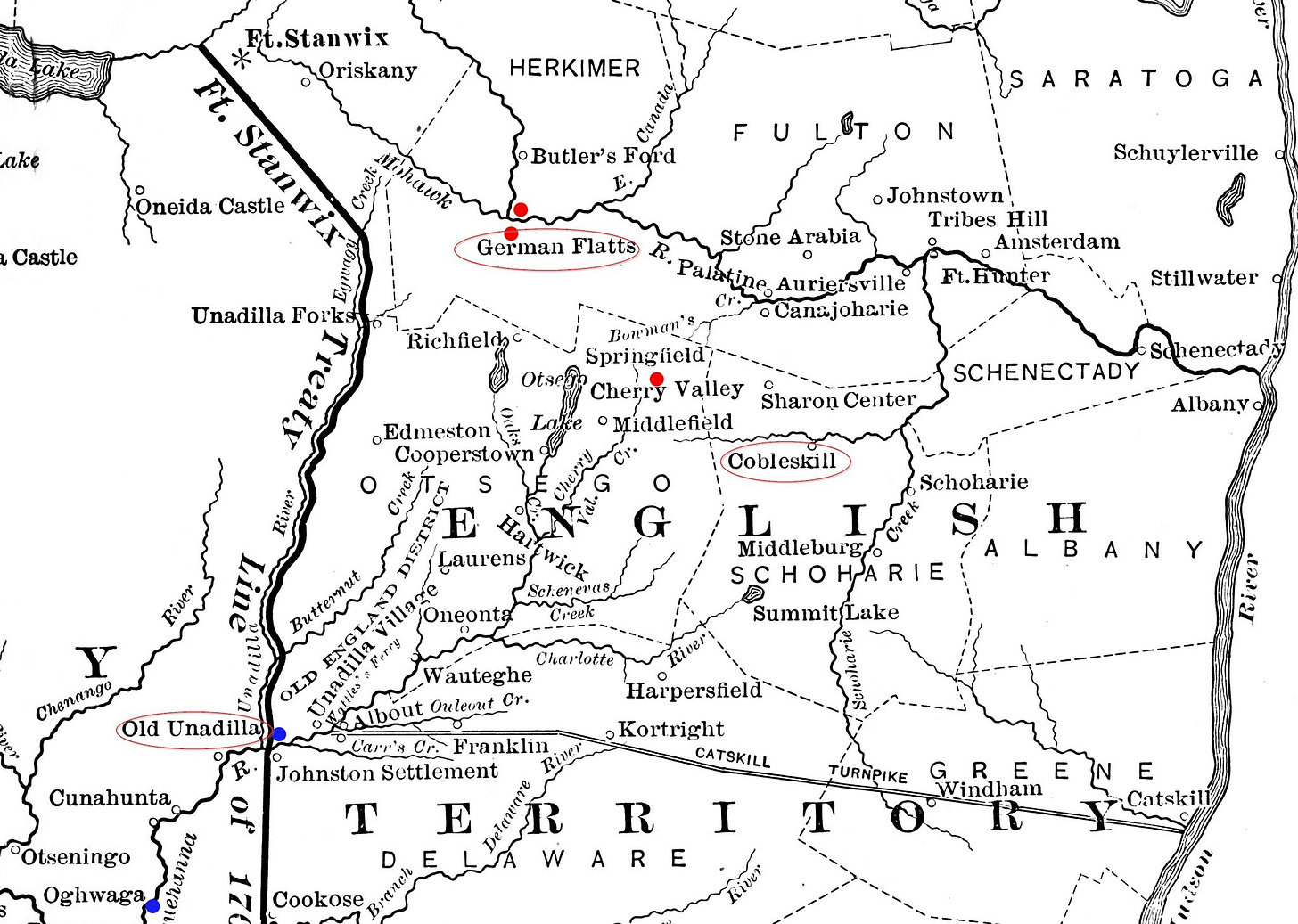

In May, Brant’s forces drew a company of continental troops into a trap at Cobleskill, luring them into massed fire. Brant’s men killed the company commander and 21 others. They proceeded to burn ten homes and stole as many livestock as they could before retreating into the woods.

More raids followed. In September, his forces struck German Flatts (Herkimer, New York). Brant led 152 men, mostly Mohawk, along with 2-300 loyalists from Butler’s Rangers. The rangers were a provincial unit of loyalists formed by John Butler, a major landowner in Western New York.

Together they burned 63 homes, along with barns and grist mills, leaving 700 people homeless and destitute. The townspeople were spared only by taking shelter in the nearby fort, since Brant’s force was not equipped with cannon to attack fortified positions. By the time a regiment of rebel militia arrived and pursued the raiders, they were unable to catch up to them.5

Their speed and lack of a baggage train allowed them to operate more like special forces than a traditional army. Brant and his marauders would strike without warning, burn, pillage, and then melt away into the wilderness. Local militia and continental army were too slow or under-manned to stop them.

The Massacre

After German Flatts, American forces organized retaliatory strikes on Onaquaga and Unadilla, destroying Brant’s base of operations. The American commander who led the attacks described Onaquaga as “the finest Indian town I ever saw; on the both sides of the River there was about 40 good houses, Square logs, Shingles & stone Chimneys, good Floors, glass windows . . .”6 Still, all of them were torched.

Rumors started circulating that a British attack on Cherry Valley was imminent, which was also supported by intelligence gathered by Oneida scouts.

After building a fort in the valley and waiting for weeks on end, Continentals stationed there had grown complacent. They believed the campaigning season was over now that winter had arrived. It was a fatal mistake.

In November 1778, a combined force of Brant’s Volunteers and Butler’s Rangers numbering between 700-800 men set up a “cold camp” (meaning no campfires) nearby, to avoid detection. Captured American scouts and careful reconnaissance near Fort Alden allowed Brant to precisely determine the disposition of the Americans.

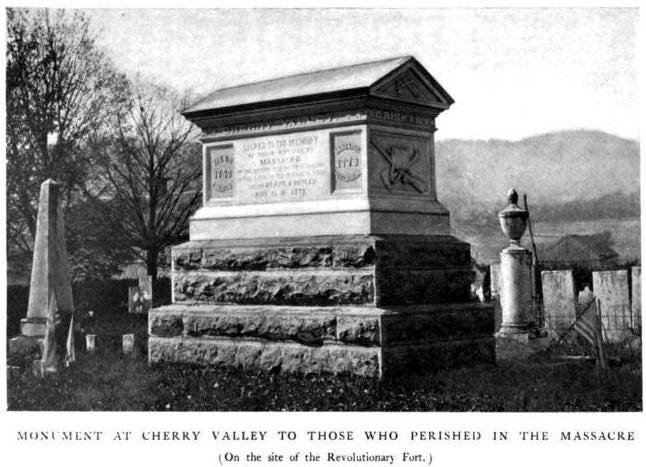

On the foggy morning of November 11, hundreds of Iroquois warriors and loyalist rangers swarmed the Fort and surrounding settlement. They caught rebels out in the open – and completely off guard. The Colonel in command was killed instantly by tomahawk to the back of the head.

Just as at German Flatts, Brant & Butler’s forces lacked artillery to breach the fort walls. But the raiders pursued anyone who was unlucky enough to have been caught out. Butler and Brant allegedly tried to restrain their men, without much success. They killed and scalped indiscriminately, including women and children, and took away at least 70 captives. Cattle and livestock were killed or driven away. Homes were fired.

As many as 32 civilians and 16 soldiers were killed in the attack, with nearly all of the bodies found mutilated. The following day, Butler sent Brant with around 40 rangers back to the area to destroy the rest of the village.

In the wake of this merciless killing, Walter Butler tried to pin the blame on Brant and his Mohawks. He wrote that:

notwithstanding my utmost Precaution and Endeavors to save the Women and Children, I could not prevent some of them falling unhappy Victims to the Fury of the Savages . . .

According to firsthand accounts, Butler was lying. His own white loyalists were just as brutal and culpable. As the ranking commander, Butler was responsible for the actions of the entire host.

Joseph Brant later helped to broker the release of captured townspeople, especially women and children. He was dismayed to learn that some of the slain families were friends of his — an indication of just how well-connected Brant was to communities in New York. Curiously, Brant spared the lives of male captives when he learned they were Free Masons, including Lieutenant Col. William Stacy.

The damage at Cherry Valley was so complete that the Americans completely abandoned the settlement.

Aftermath

News of the devastation wrought by Brant & Butler’s lightning raids went right up the chain of command. As early as July of 1778, Washington complained to General Philip Schuyler about Brant’s “considerable mischief on the North East corner of Pennsylvania.”

In the fall, Washington wrote: “It is in the highest degree distressing, to have our frontier so continually harassed by this collection of Banditti under Brand and Butler.”7

In 1779, Washington put out a bounty for Brant’s capture, and then ordered General John Sullivan of New Hampshire to lead colonial forces against Iroquois communities in Northern Pennsylvania. His order read:

“The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the six nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible . . . I would recommend that some post in the center of the Indian Country should be occupied with all expedition, with a sufficient quantity of provision, whence parties should be detached to lay waste all the settlements around with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun but destroyed.”8

Washington’s letter was unambiguous in its endorsement of total war. Sullivan’s mission, true to his orders, caused immense destruction throughout Iroquois territory, much greater than anything Brant and his volunteers had wrought in 1778. The punitive campaign didn’t stop Brant’s forces from continuing to wage guerrilla war.

The British historian Michael Johnson called Brant the "scourge of the American settlements of New York and Pennsylvania.” While this has a ring of truth to it, the reality is far more complicated.

The Iroquois Nations as a whole were not simply pawns or victims in this conflict, but participants with agency. Brant, though controversial at the time, has been praised as recognizing shifting sentiments among the Americans and working with what he believed to be the best partner for the future of his people.

When a white army battles Indians and wins, it is called a great victory, but if they lose, it is called a massacre.

Cheeseekau (Chiksika) Shawnee Chief of Kispoko Div. and older brother of Tecumseh

"British Evacuation of Boston, 1776," Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, accessed June 18, 2024, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/british-evacuation-boston-1776.

American Battlefield Trust, "Saratoga," American Battlefield Trust, accessed May 29, 2024, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/saratoga.

"Sir Guy Carleton," George Washington's Mount Vernon, accessed June 18, 2024, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/sir-guy-carleton.

Andrew Arnold Lambing et al., "Allegheny County: Its Early History and Subsequent Development: From the Earliest Period till 1790," Historic Pittsburgh Text Collection, University of Pittsburgh, accessed September 12, 2013, https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt:00aeah9780m/viewer.

Harry Schenawolf, "Attack on German Flatts, 1778," Revolutionary War Journal, accessed June 18, 2024, https://revolutionarywarjournal.com/attack-on-german-flatts-1778/.

Karim M. Tiro, "The Material Culture of Oquaga in the Collection of the Peabody Essex Museum," accessed July 10, 2024, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14394/50241.

George Washington, “From George Washington to Brigadier General Edward Hand, 16 November 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 29, 2024, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-18-02-0167.

From George Washington to Major General John Sullivan, 31 May 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0661 (emphasis in original).