The Faked Kidnapping of Martin Luther

For nearly a year, Martin Luther was hidden away in a castle, where he unintentionally laid the groundwork for revolution.

Martin Luther: 16th century reformer, professor, churchman, and writer of Christian slam poetry.1 Luther published his famous 95 Theses in 1517, which helped spark the Protestant Reformation, arguably one of the biggest transformations of Western Europe in a thousand years.

But for Martin Luther, the early days were dangerous. It turns out, pissing off the Catholic establishment in early modern Europe can net you a lot of enemies.

Controversial Words

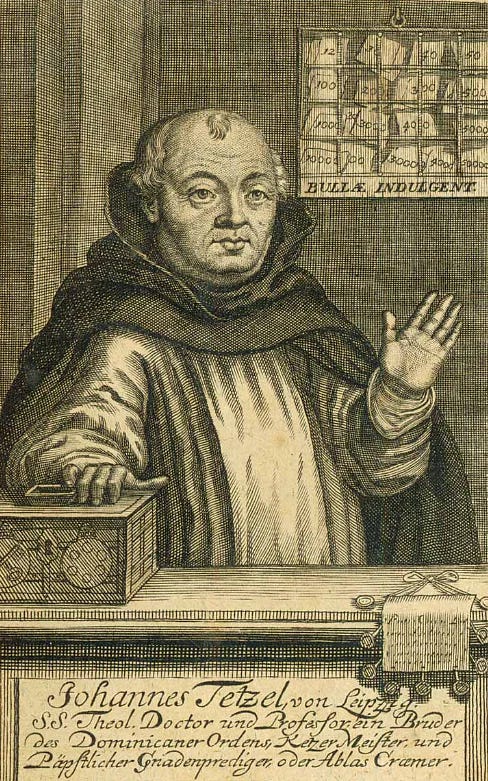

Martin published with the intention to get into an academic debate about indulgences (which were like cash donation for the remission of certain sins — usually purchased on behalf of people who were already dead). His writing was in some ways deferential to the church, but pointedly criticized a Dominican friar, Johann Tetzel, for preaching to his followers that these were fast-track tickets into heaven.2

Why was Tetzel preaching in this way? He’d been appointed by the church in Rome to help raise money for the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica, and the sale of indulgences was a means to that end — though only about half of the money collected went to the Church.3

Martin Luther’s work pointed out serious issues with the practice — but there were other lines which would have raised eyebrows, including this one:

86. Why does not the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?4

This was a jab at the Pope himself. Marcus Licinius Crassus was the most absurdly wealthy guy in Republican Rome (and a contemporary of Julius Caesar), who essentially paid for his power and influence with cold hard cash. To be compared to Crassus was never a compliment.

Theses 56-66 accused the Church of marketing indulgences particularly to the rich, who could afford paying good money to get to the front of the line. Some things never change.

66. The treasures of the indulgences are nets with which they now fish for the riches of men.5

We could talk all day about how he skewered the underpinnings of church policies affecting practically every Christian Kingdom in Western Europe. How did the church take his constructive feedback?

Blowback

Martin’s message, while often supportive, was incisively critical of the business of faith. Thanks to the printing press, his ideas were translated, reprinted, and distributed throughout Europe. He got way more than he bargained for. Big Catholicism was not happy.

After Luther refused to recant his positions in January 1521, Pope Leo X excommunicated him. In practice, this meant Martin couldn’t receive sacraments (communion confession, etc.) from the church, and more or less cut him off from religious salvation.

By this point, he was under serious threat of death. Martin Luther was offered another chance to “take it back” during an audience with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in Worms. Again, he refused.

Charles had him declared an outlaw, heretic, and enemy of the state. A warrant was put out for Martin’s arrest, and the Edict of Worms made it an actual crime to give him food & shelter — and lifted any legal consequences for killing him. They also, weirdly, gave him a head start to get the hell out of dodge.

Forced Sabbatical

Frederick III (also known as ‘the Wise’), who was Prince-Elector of Saxony, thought he could take advantage of the situation. He decided to place Martin Luther under his personal protection, and arranged to have him “abducted” after departing Worms. Frederick was rightly concerned that he’d be murdered or captured on the road.

Initially, it wasn’t so much that Frederick believed in his theological propositions. Since Wittenburg was located within Saxony, Luther was one of his subjects, and he felt Luther deserved fair treatment under the law.

While he was on the road home to Wittenburg, a company of masked horsemen (Frederick’s troops) dressed in the garb of highway robbers staged an attack and snatched Martin Luther. They escorted him to the Wartburg in secret.6

The Wartburg is a castle situated on a hilltop just outside of Eisenach, a charming little industrial town nestled in the Thuringian hills of central Germany. Eisenach is also the birthplace of Bach and the home of the quirky East German Wartburg Automobile.

Given his newfound outlaw status, Martin Luther needed to lie low. For almost a year, he grew out his hair and dressed in different clothing. He lived in a small room at the Wartburg under an assumed name: Junker Jörg (the Knight George, or Squire George). I think we can all agree that this is a laughably bad pseudonym.

Bad aliases aside, forced exile wasn’t a cakewalk for Luther, who in letters complained of loneliness, self doubt, depression, poor digestion, and nightmarish visions of the devil. But Frederick’s plan worked. Many people, including his supporters, thought that he was dead.

During his residence, Luther and a small group of scholars translated the New Testament into German from the original Greek — which had a substantial impact on standardizing written and spoken German.7 He’d work on this project for years, and after his best-selling New Testament dropped in 1522, the first complete Luther-translated Bible was released in 1534.8

Luther also widened his targets in his writings about church excesses and doubled-down on the views he’d been asked to give up. By the time he ventured out to Wittenburg in March of 1522, his ideas were popular enough that his safety was less of a concern.

Post Exile

Martin Luther continued to seek the protection of Saxony’s Princes even after his benefactor Frederick III died in 1525. Frederick’s successor (his brother) even became a Lutheran himself.

Charles V was likely reluctant to break the peace and pursue Martin Luther by force, which would have violated the sovereignty of Saxony and exploded the complicated political patchwork of the Holy Roman Empire. Frederick had also voted for Charles in the 1519 imperial election. Conveniently, he had also allegedly instructed his soldiers not to tell him where they had actually taken Martin — which gave him some plausible deniability.9

Within a few years, partly fueled by Martin’s writings, the German Peasant Revolt broke out. This was the biggest popular uprising in Europe prior to the French Revolution, more than 250 years later.10 Hundreds of thousands died. It would be the first of many conflagrations in the next 150 years linked to the Protestant Reformation. Luther’s influence on these later events is well worth examining.

"Martin Luther and Music," Musée Protestant, accessed June 18, 2024, https://museeprotestant.org/en/notice/martin-luther-and-music/.

Hans J. Hillerbrand, "Martin Luther: The Indulgences Controversy," Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed June 18, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Martin-Luther/The-indulgences-controversy.

Joshua J. Mark, "Johann Tetzel," World History Encyclopedia, accessed June 18, 2024, https://www.worldhistory.org/Johann_Tetzel/.

Hillerbrand, "Martin Luther: The Indulgences Controversy."

"Martin Luther's 95 Theses," Famous Trials, accessed June 18, 2024, https://www.famous-trials.com/luther/296-theses.

"Martin Luther Kidnapped," Reformation Art, accessed June 18, 2024, https://www.reformationart.com/martin-luther--17-kidnapp.html.

It is an important distinction to mention the Greek here because there were other German translations of the New Testaments already in circulation which themselves were based on later Latin interpretations. Luther’s utilized both St. Jerome’s original vulgate, Greek, and Hebrew texts. So technically speaking, Martin Luther’s edition was not the first.

"Early Printing in Wittenberg," Forum Ancient Coins, accessed June 18, 2024, https://www.forumancientcoins.com/historia/earlyprinting/wittenberg.htm.

"The Wartburg: Fighting the Devil - Luther and the Wartburg," See Art V, accessed June 18, 2024, https://seeartv.com/en/the-wartburg-fighting-the-devil-luther-and-the-wartburg.html.

Martin Empson, "The German Peasants’ War Was Europe’s Biggest Social Revolt Before the French Revolution," Jacobin, December 1, 2023, accessed June 18, 2024, https://jacobin.com/2023/12/german-peasants-war-feudalism-class-conflict-reformation.